If you were to visit the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau a thousand years ago, you’d find conditions remarkably familiar to the present. The climate was warm but drier than today. There were large populations of Indigenous people known as the Fremont, who hunted and grew crops in the area. With similar climate and moderate human activity, you might expect to see the types of wildfires that are now common to the American West: infrequent, gigantic and devastating. But you’d be wrong.

In a new study led by the University of Utah, researchers found that the Fremont used small, frequent fires, a practice known as cultural burning, which reduced the risk for large-scale wildfire activity in mountain environments on the Fish Lake Plateau—even during periods of drought more extreme and prolonged than today.

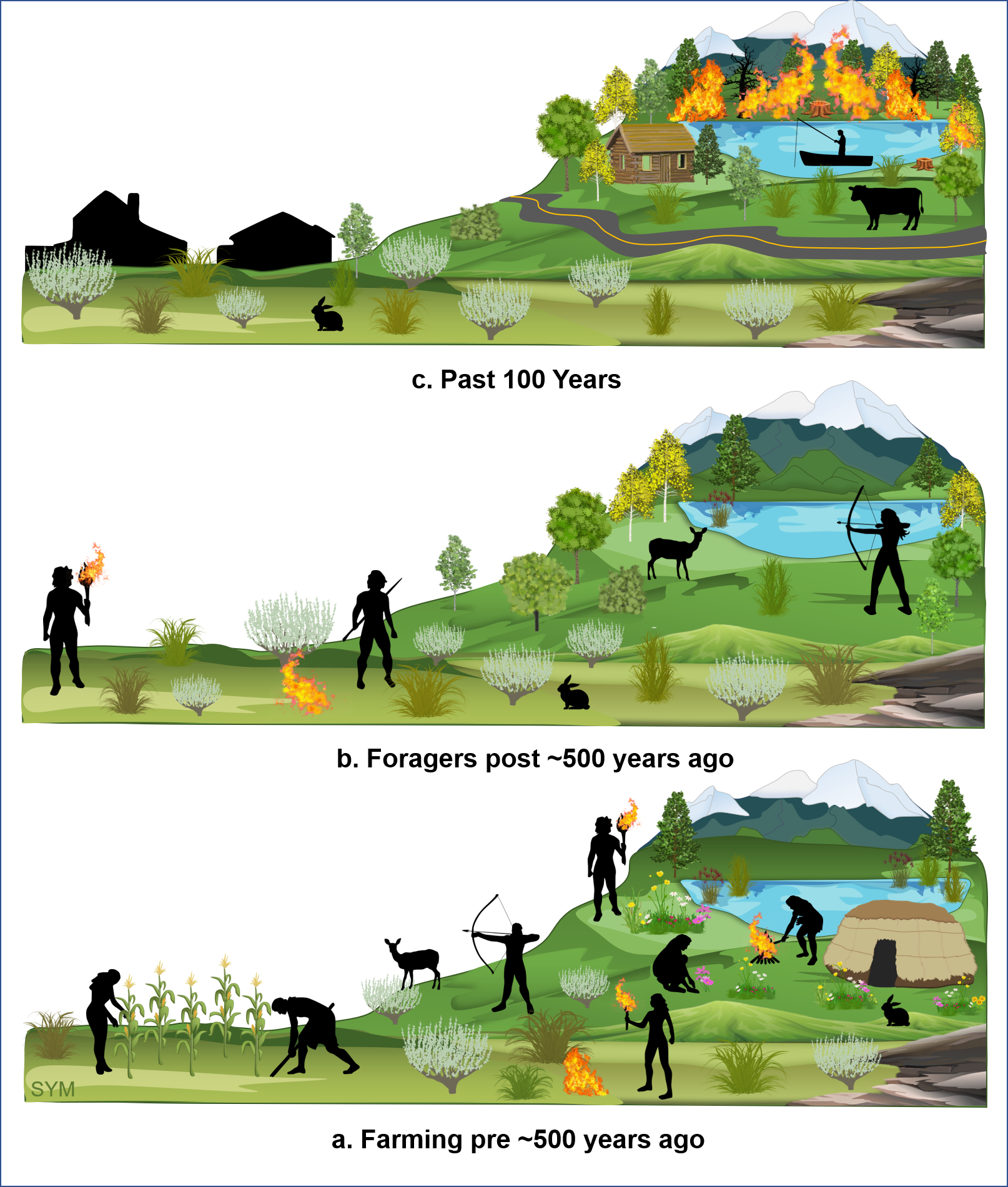

PHOTO CREDIT: S. Yoshi Maezumi

A schematic of what the authors think the landscape and human activity were like over the last 1,200 years in the Fish Lake Plateau region. A) 1,200 to 500 years ago, a high density of people hunting, harvesting wild plants and cultivating crops. They controlled the fire regime with cultural burning that created a landscape dominated by the plants for sustenance rather than dense forest typical of the elevation. B) 500-100 years ago, farming activity ceased abruptly. Forgers and hunters, ancestors of the Ute and Paiute, still practiced cultural burning, although much less than farmers had previously. Trees began to slowly expand their range. C) Past 100 years, European settlers made cultural burning illegal, and the landscape became dominated by forests, setting up conditions for catastrophic wildfires.

Download Full-Res ImageThe researchers compared lake sediment, tree ring data and archaeological evidence to reconstruct a 1,200 history of fire, climate, and human activity of the Fish Lake Plateau, a high-elevation forest in central Utah in the United States. They found that frequent fires occurred between the years 900 and 1400, a period of intense farming activity in the region. Prehistoric cooking hearths and pollen preserved in lake sediment show that edible plant species dominated the landscape during this period, indicating that Fremont people practiced cultural burning to support edible wild plants, including sunflowers, and other crops. Large-scale farming ceased after the year 1400. Hunters and foragers, ancestors of the Ute and Paiute, continued to burn, although less frequently than during the farming period. After Europeans made cultural burning illegal, the ecosystem returned to be dominated by a thick forest of trees.

“When you have people burning frequently, they’re reducing the number of surface fuels present on the landscape. It makes it much more difficult for a lightning fire to reach up to the canopy and burn down the entire forest,” said Vachel Carter, postdoctoral research assistant at the U and lead author of the study. “Now we have an environment dominated by trees in a very dry environment, which are conditions prime for megafires. Is this a result of climate change? Definitely. But in the case at Fish Lake, it could also be attributed to a lack of cultural burning.”

For millennia through the present, Indigenous people across North America have used cultural burning to drive game, ease travel, clear vegetation for fields and enhance the regrowth of edible plants. European settlers banned the practice in favor of fire suppression, the strategy that’s dominated forest management since the turn of the 20th century.

PHOTO CREDIT: Vachel Carter

Vachel Carter, lead author of the study, at Fish Lake during the winter while collecting lake core samples.

Download Full-Res Image“All over North America, humans have always modified fire regimes to benefit themselves and their families,” said Brian Codding, associate professor of anthropology at the U and senior author of the paper. “Cultural burning is something that needs to be considered when people are talking about how to manage forests, just like in the Fish Lake National Forest.”

The paper published April 14, 2021, in the Nature journal Communications Earth and Environment.

It takes a village

The study is the first in the region to combine charcoal, pollen, tree ring and archeological site data together to assess the human influence on prehistoric wildfires. The multiple disciplines allowed the researchers to make connections that would otherwise have been impossible.

“This is really showing us something that’s kind of invisible otherwise,” said Codding. “People have been trying to look at human impacts on fire regimes all over the place, and it’s really hard. Because the changes might be really subtle, or our records just aren’t fine-grained enough to record the types of changes that can reveal it.”

Colleagues from Utah State University and Brigham Young University contributed tree ring data that document how the climate has shifted over time. Thick rings mean that the tree grew rapidly, indicating there was more moisture available. Narrow rings represent a slow growth year due to less moisture, a signature that can record periods of drought. For this study, they established a climatological timeline for the Fish Lake area.

PHOTO CREDIT: Vachel Carter

Mitchell Power of the Natural History Museum of Utah and co-author of the study, pulls out a freeze corer, a device used to collect lake sediment.

Download Full-Res ImageCarter analyzed the contents of ancient sediments to reconstruct past worlds. Detritus from the local environment blows over the lake and settles at the bottom, building up layers as time passes. Each layer provides a snapshot of what the surrounding area was like at a particular time. She used charcoal as a proxy for fire abundance—more charcoal means more frequent fire—and analyzed pollen grains to determine what plant species dominated and compared how those changed over the last 1,200 years.

Codding and colleagues counted the number of sites that were occupied, using radiocarbon dates on items found at dwelling sites to establish when people were there. They also used food remnants in cooking hearths to establish the types of food people were eating. They analyzed sites within modern-day Sevier County, the area around and including Fish Lake, the ancestral lands of the Ute and Paiute Tribes.

“From the cooking hearths found at Fish Lake, we got an indication of what people were eating, and when they were eating it. We knew that they were eating food in the sunflower family, the grass family, and the sedge family, all these plants that don’t naturally dominate a high elevation forest,” said Carter. “I counted the pollen from those species in the sediment cores and, sure enough, when the Fremont were present, those same plant species were present in much higher abundances than when the Fremont were absent.”

“This piece really pulls the study together for linking how people living at this area, at higher densities, were actually modifying the environment to increase the resources that were available to them,” Codding said.

Cultural burning for Pando

PHOTO CREDIT: Vachel Carter

A close-up of sediment pulled from Fish Lake. Researchers analyzed microscopic pollen and charcoal to understand what the environment was like going back thousands of years.

Download Full-Res ImageIn Utah, many forests could benefit from frequent, smaller fires to mitigate wildfire risk. Perhaps one of the most urgent is in the Fish Lake National Forest that guards Pando, a stand of 47,000 aspen tree clones and the most massive organism on Earth. Pando has sat at the south end of Fish Lake for thousands of years, at least—some say the organism is a million years old. In recent years, the beloved grove has been shrinking. Low severity fires may help Pando, and other Utah forests, stay healthy.

“Fuels on the Fish Lake landscape are at the highest that they’ve been in the last 1,200 years. The climate is much warmer than it was in the past. Our droughts have not been as intense as we’ve seen in the past, but they’re on their way,” Carter said. “The Fremont likely created long-lasting legacies on the Fish Lake Plateau through their cultural burning. Moving forward, ‘good fire,’ like prescribed fire, will be needed to mitigate against wildfire risk.”

Other authors of the study include the following researchers from the University of Utah: Andrea Brunelle, Department of Geography and the Global Change and Sustainability Center (GCSC); Mitchell J. Power, Natural History Museum of Utah and the GCSC; Isaac Hart, Department of Geography and the Archaeological Center; and Simon Brewer, Department of Geography. Authors from other institutions include R. Justin DeRose and Erick Robinson, Utah State University; Matthew F. Bekker, Brigham Young University; Jerry Spangler, Colorado Plateau Archaeological Alliance; Mark Abbott, University of Pittsburg; and S. Yoshi Maezumi, The University of Amsterdam.

The paper, “Legacies of Indigenous land use shaped past wildfire regimes in the Basin-Plateau Region, USA,” is available under DOI: 10.1038/s43247-021-00137-3.