Today’s marine giants—such as blue and humpback whales—routinely make massive migrations across the ocean to breed and give birth in waters where predators are scarce, with many congregating year after year along the same stretches of coastline. Now, new research from a team of scientists—including researchers with the University of Utah (Natural History Museum of Utah and Department of Geology & Geophysics), Smithsonian Institution, Vanderbilt University, University of Nevada, Reno, University of Edinburgh, University of Texas at Austin, Vrije Universiteit Brussels, and University of Oxford—suggests that nearly 200 million years before giant whales evolved, school bus-sized marine reptiles called ichthyosaurs may have been making similar migrations to breed and give birth together in relative safety.

The findings, published today in the journal Current Biology, examine a rich fossil bed in the renowned Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park (BISP) in Nevada’s Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest, where many 50-foot-long ichthyosaurs (Shonisaurus popularis) lay petrified in stone. Co-authored by Randall Irmis, NHMU chief curator and curator of paleontology, and associate professor, the study offers a plausible explanation as to how at least 37 of these marine reptiles came to meet their ends in the same locality—a question that has vexed paleontologists for more than half a century.

“We present evidence that these ichthyosaurs died here in large numbers because they were migrating to this area to give birth for many generations across hundreds of thousands of years,” said co-author and Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History curator Nicholas Pyenson. “That means this type of behavior we observe today in whales has been around for more than 200 million years.”

Over the years, some paleontologists have proposed that BISP’s ichthyosaurs—predators resembling oversized chunky dolphins which have been adopted as Nevada’s state fossil—died in a mass stranding event such as those that sometimes afflicts modern whales, or that the creatures were poisoned by toxins such as from a nearby harmful algal bloom. The problem is that these hypotheses lack strong lines of scientific evidence to support them.

To try to solve this prehistoric mystery, the team combined newer paleontological techniques such as 3D scanning and geochemistry with traditional paleontological perseverance by poring over archival materials, photographs, maps, field notes and drawer after drawer of museum collections for shreds of evidence that could be reanalyzed.

Although most well-studied paleontological sites excavate fossils so they can be more closely studied by scientists at research institutions, the main attraction for visitors to the Nevada State Park-run BISP is a barn-like building that houses what researchers call Quarry 2, an array of ichthyosaurs that have been left embedded in the rock for the public to see and appreciate. Quarry 2 has partial skeletons from an estimated seven individual ichthyosaurs that all appear to have died around the same time.

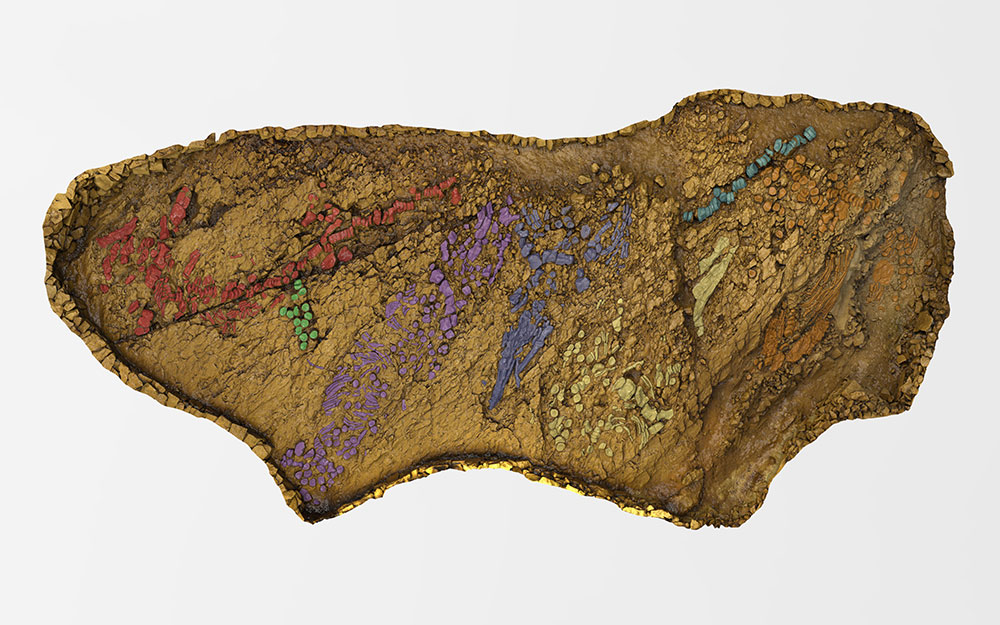

“When I first visited the site in 2014, my first thought was that the best way to study it would be to create a full-color, high-resolution 3D model,” said lead author Neil Kelley, an assistant professor at Vanderbilt University. “A 3D model would allow us to study the way these large fossils were arranged in relation to one another without losing the ability to go bone by bone.”

To do this, the research team collaborated with Jon Blundell, a member of the Smithsonian Digitization Program Office’s 3D Program team, and Holly Little, informatics manager in the museum’s Department of Paleobiology. While the paleontologists were physically measuring bones and studying the site using traditional paleontological techniques, Little and Blundell used digital cameras and a spherical laser scanner to take hundreds of photographs and millions of point measurements that were then stitched together using specialized software to create a 3D model of the fossil bed.

“Our study combines both the geological and biological facets of paleontology to solve this mystery,” said Irmis. “For example, we examined the chemical make-up of the rocks surrounding the fossils to determine whether environmental conditions resulted in so many Shonisaurus in one setting. Once we determined it did not, we were able to focus on the possible biological reasons.”

The team collected tiny samples of the rock surrounding the fossils and performed a series of geochemical tests to look for signs of environmental disturbance. One test measured mercury, which often accompanies large-scale volcanic activity, and found no significantly increased levels. Other tests examined different types of carbon and determined that there was no evidence of sudden increases in organic matter in the marine sediments that would result in a dearth of oxygen in the surrounding waters (though, like whales, the ichthyosaurs breathed air).

These geochemical tests revealed no signs that these ichthyosaurs perished because of some cataclysm that would have seriously disturbed the ecosystem in which they died. The research team continued to look beyond Quarry 2 to the surrounding geology and all the fossils that had previously been excavated from the area.

The geologic evidence indicates that when the ichthyosaurs died, their bones eventually sank to the bottom of the sea, rather than along a shoreline shallow enough to suggest stranding, ruling out another hypothesis. Even more telling though, the area’s limestone and mudstone was chock-full of large adult Shonisaurusspecimens, but other marine vertebrates were scarce. The bulk of the other fossils at BISP come from small invertebrates such as clams and ammonites (spiral-shelled relatives of today’s squid).

“There are so many large, adult skeletons from this one species at this site and almost nothing else,” said Pyenson. “There are virtually no remains of things like fish or other marine reptiles for these ichthyosaurs to feed on, and there are also no juvenile Shonisaurus skeletons.”

The researchers’ paleontological dragnet had eliminated some of the potential causes of death and started to provide intriguing clues about the type of ecosystem these marine predators were swimming in, but the evidence still didn’t clearly point to an alternative explanation.

The research team found a key piece of the puzzle when they discovered tiny ichthyosaur remains among new fossils collected at BISP and hiding within older museum collections. Careful comparison of the bones and teeth using micro-CT x-ray scans at Vanderbilt University revealed that these small bones were in fact embryonic and newborn Shonisaurus.

“Once it became clear that there was nothing for them to eat here, and there were large adult Shonisaurusalong with embryos and newborns but no juveniles, we started to seriously consider whether this might have been a birthing ground,” said Kelley.

Further analysis of the various strata in which the different clusters of ichthyosaur bones were found also revealed that the ages of the many fossil beds of BISP were separated by at least hundreds of thousands of years, if not millions.

“Finding these different spots with the same species spread across geologic time with the same demographic pattern tells us that this was a preferred habitat that these large oceangoing predators returned to for generations,” said Pyenson. “This is a clear ecological signal, we argue, that this was a place that Shonisaurusused to give birth, very similar to today’s whales. Now we have evidence that this sort of behavior is 230 million years old.”

The team said the next step for this line of research is to investigate other ichthyosaur and Shonisaurus sites in North America with these new findings in mind to begin to recreate their ancient world by perhaps looking for other breeding sites or for places with greater diversity of other species that could have been rich feeding grounds for this extinct apex predator.

“One of the exciting things about this new work is that we discovered new specimens of Shonisaurus popularis that have really well-preserved skull material,” Irmis said. “Combined with some of the skeletons that were collected back in the 1950s and 1960s that are at the Nevada State Museum in Las Vegas, it’s likely we’ll eventually have enough fossil material to finally accurately reconstruct what a Shonisaurus skeleton looked like.”

The 3D scans of the site are now available for other researchers to study and for the public to explore via the open-source Smithsonian’s Voyager platform, which is developed and maintained by Blundell’s team members at the Digitization Program Office, and anyone can take a deeper dive with the 3D model at: https://3d.si.edu/enter-sea-dragon

“Our work is public,” said Blundell. “We aren’t just scanning sites and objects and locking them up. We create these scans to open up the collection to other researchers and members of the public who can’t physically get to a museum.”

This research was conducted under research permits issued by the U.S. Forest Service and Nevada State Parks, and was supported by funding from the Smithsonian, University of Nevada, Reno, Vanderbilt University, and University of Utah.

Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park is part of Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest in the Shoshone Mountains of west-central Nevada. It is within the ancestral homelands of the Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone peoples.