In 2018, the Camp Fire ripped through the town of Paradise, California at an unprecedented rate. Officials had prepared an evacuation plan that required three hours to get residents to safety. The fire, bigger and faster than ever before, spread to the community in only 90 minutes.

As climate change intensifies, wildfires in the West are behaving in ways that were unimaginable in the past—and the common disaster response approaches are woefully unprepared for this new reality. In a recent study, a team of researchers led by the University of Utah proposed a framework for simulating dire scenarios, which the authors define as scenarios where there is less time to evacuate an area than is required. The paper, published on April 21, 2021, in the journal Natural Hazards Review, found that minimizing losses during dire scenarios involves elements that are not represented in current simulation models, among them improvisation and altruism.

“The world is dealing with situations that exceed our worst-case scenarios,” said lead author Thomas Cova, professor of geography at the U. “Basically we’re calling for planning for the unprecedented, which is a tough thing to do.”

PHOTO CREDIT: Cova et. al. (2021) Nat Hazards Rev

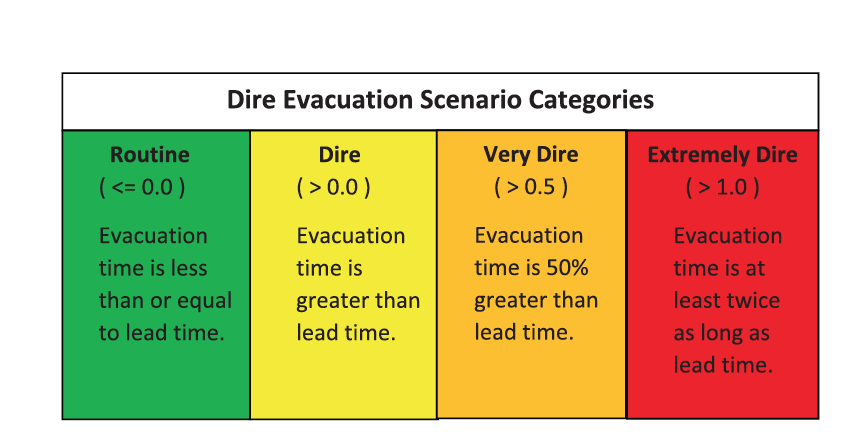

Dire evacuation scenario category based on a score.

Download Full-Res ImageMost emergency officials in fire-prone regions develop evacuation plans based on the assumptions that wildfires and residents will behave predictably based on past events. However, recent devastating wildfires in Oregon, California and other western states have shown that those assumptions may no longer hold.

“Wildfires are really becoming more unpredictable due to climate change. And from a psychological perspective, we have people in the same area being evacuated multiple times in the past 10 years. So, when evacuation orders come, people think, ‘Well, nothing happened the last few times. I’m staying,’” said Frank Drews, professor of psychology at the U and co-author of the study. “Given the reality of climate change, it’s important to critically assess where we are and say, ‘Maybe we can’t count on certain assumptions like we did in the past.’”

How to predict the unprecedented

The framework allows planners to create a dire wildfire scenario—when the lead time, defined as the time before the fire reaches a community to respond, is less than the time required to evacuate. The authors developed a scoring system that categorizes each scenario as routine, dire, very dire or extremely dire based on many different factors.

PHOTO CREDIT: Cova et. al. (2021) Nat Hazards Rev

Anatomy of a dire scenario due to sudden increase of fire spread rate. Red line is an extremely dire scenario, yellow is dire, and green is routine.

Download Full-Res ImageOne big factor affecting the direness is the ignition location, as one closer to a community offers less time than one farther away. A second major factor is the wildfire detection time. During the day, plumes of smoke can cue a quick response, but if it starts at night when everyone is asleep, it could take longer to get people moving. Officials may delay their decisions to avoid disrupting the community unnecessarily, but a last-minute evacuation order can cause traffic jams or put a strain on low-mobility households.

Alert system technologies can create dire circumstances if residents do not receive the warning in time due to poor cellphone coverage or low subscription rates to reverse 911 warning systems. If the community has many near misses with wildfire, the public’s response could be to enact a wait-and-see approach before they leave their homes.

Using a dire scenario dashboard, the user assigns various factors an impediment level—low, minor or major—that can change at any point to lessen or increase a situation’s direness.

“Usually when we run computer simulations, nothing ever goes wrong. But in the real world, things can get much worse half-way through an evacuation,” said Cova. “So, what happens when you don’t have enough time? The objective switches from getting everyone out to instead minimizing casualties. It’s dark.”

“More people began working remotely from home during the pandemic, which then led to them moving out of large cities into rural areas,” explained assistant professor Dapeng Li of the South Dakota State University Department of Geography and Geospatial Sciences, a co-author and U alumnus who helped develop the computer simulations. “These rural communities typically have fewer resources and face challenges in rapidly evacuating a larger number of residents in this type of emergency situation.”

Reducing dire scenarios

Simulating dire wildfire scenarios can improve planning and the outcomes in cases where everything goes wrong. For example, creating fire shelters and safety zones inside of a community can protect residents who can’t get out, while reducing traffic congestion for others who can evacuate. During the 2018 Camp Fire, people improvised temporary refuges in parking lots and community buildings. Modeling could help city planners construct permanent safety areas ahead of time.

Common human responses during wildfires are improvisations and creative thinking, which are difficult to model but can be literally lifesaving. For example, during the 2020 Creek Fire in California, a nearby military base sent a helicopter to rescue trapped campers. Another crucial component is individuals helping others, such as people giving others rides or warning neighbors who missed the official alert. During the Camp Fire, Joe Kennedy used his bulldozer to singlehandedly clear abandoned cars that were blocking traffic.

“It is very common for families and neighbors to assume a first responder role and help each other during disasters,” said Laura Siebeneck, associate professor of emergency management and disaster science at the University of North Texas and co-author of the study. “Many times, individuals and groups come together, cooperate, and improvise solutions as needed. Though it is difficult to capture improvisation and altruism in the modeling environment, better understanding human behavior during dire events can potentially lead to better protective actions and preparedness to dire wildfire events.”

Studying and modeling dire scenarios is necessary to improve the outcomes of unprecedented changes in fire occurrence and behavior. This study is the first attempt to develop a simulation framework for these scenarios, and more research is needed to incorporate the unpredictable elements that create increasingly catastrophic wildfires.