This year, Utah’s students are entering revolutionary science classes. It’s not just about COVID-19—the Utah State Board of Education approved new science standards that shift the learning framework from a lecture-based model to one where students think and act like scientists as they explore real-world phenomena. Graduates of the University of Utah Master’s of Science for Secondary School Teachers (MSSST) program are uniquely prepared to meet the challenge.

The program supports teachers who want to earn a master’s of science while still actively teaching in their classrooms. Every other summer, participants enroll to earn their project-based Master’s of Science with an emphasis in teaching. The scientific disciplines vary between cohorts, but the aim remains consistent—to master in-depth content knowledge, learn pedagogical techniques, and develop leadership skills. The program culminates in an intensive 8-week research experience with a U scientist and presents their findings to a committee. The students will graduate with their M.S. in December.

“Because science teachers are in high demand, many find themselves teaching in ‘out-of-field’ areas; teachers trained as biologists are expected to teach physics, etc.,” said Jessica Cleeves, program director of MSSST and associate director for Equitable Instruction & Clinical Support at the U’s Center for Science and Mathematics Education. “MSSST isn’t about writing lesson plans. It develops educator capacity by building teacher’s content expertise and research experience. It isn’t easy. We don’t give people fish. We cultivate exceptional science educators.”

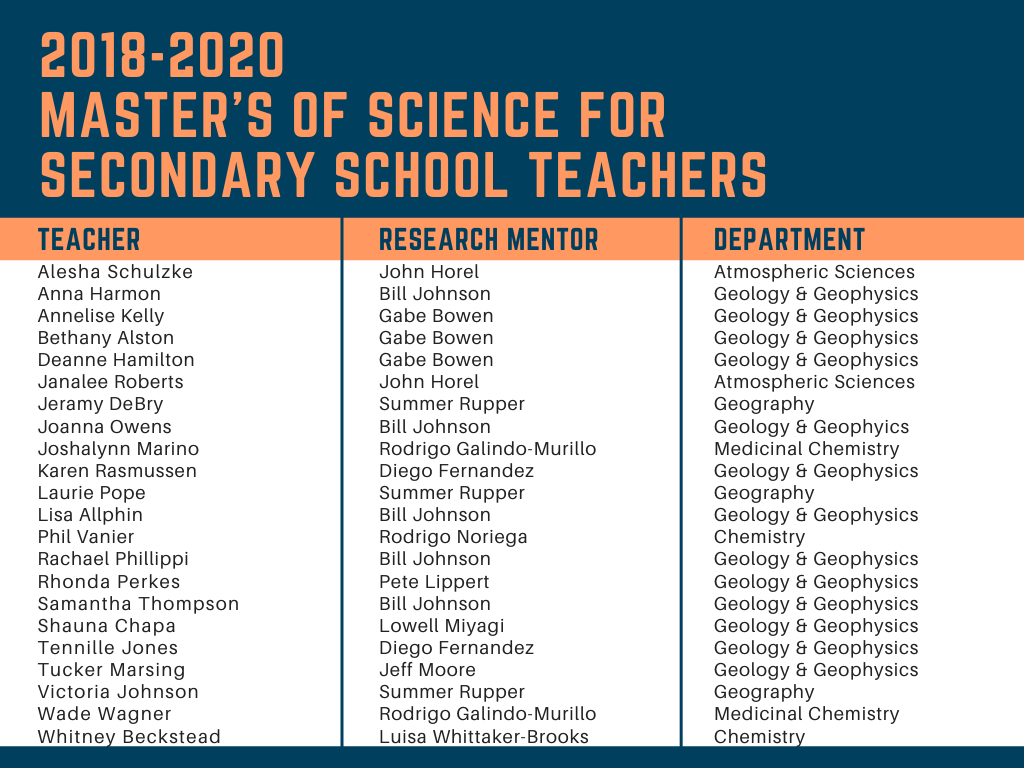

The 2018-2020 MSSST cohort of 22 teachers focused on earth sciences through significant support from the College of Mines and Earth Sciences (CMES).

“It’s been a really important program to create awareness of the importance of the earth sciences in Utah for middle and high schoolers. The extractive industries are a large part of the state’s exports, and preserving land and water resources are incredibly important for Utah’s future,” said Darryl Butt, dean of CMES. “It’s a wonderful program and a great non-traditional outreach tool.”

After two years of rigorous coursework, COVID-19 hit and made the in-person lab- or field-based experienceimpossible. Through teachers’ resilience, faculty’s flexibility and commitment, and a tirelessly creative program director, the MSSST graduates are entering the school year prepared to transfer virtual research skills into their own modified teaching environments.

“Science is about problem solving and constantly reassessing your assumptions. The program teaches that it’s OK to invite students into the productive struggle,” Cleeves said “These teachers have lived through that experience in this program. The timing of this is both painful and powerful.”

Research in a socially distanced world

As faculty strove to understand restrictions and opportunities, Cleeves scrambled to identify new scientists, brainstorm potential virtual projects, and set guidelines about remote mentoring. Ultimately, 14 U faculty from many disciplines stepped up, with some taking on more students than they had initially planned. Gabriel Bowen, professor of geology and geophysics, mentored three MSSST students over the summer.

“It’s a pretty unique opportunity for the teachers, but also for the faculty to have this structured program with highly motivated secondary school science teachers already at the U, engaged in science training,” Bowen said. “We benefit from having an extra set of eyes, hands, body and brain on site, while provide the enriching experience.”

For Bethany Alston, biology teacher at Riverton High School, the MSSST program was a dream come true. She earned a bachelor’s of science in biology, but was teaching earth sciences to 7th graders at the time.

“When I started MSSST, my goal was to get a masters and bulk up my scientific knowledge. That goal has expanded astronomically,” Alston said. “My driving force this year is to put real science in the hands of kids. They don’t have to become scientists, or even be super interested in science. But I want to teach them how to identify truth.”

Alston worked with Bowen, whose lab focuses on how carbon and water cycles through ecosystems. Alston’s piece of that research was to nail down when forests transitioned between seasons by measuring the greenness of a given area. She had planned to go on ten day road trip to collect data from sites around the United States. The pandemic forced Alston and Bowen to pivot to a virtual project using a database that stores images from phenocams, a technology that takes digital, repeated images of ecosystems.

“At first I was frustrated because that wasn’t what I signed up for. Over time, I realized that it helped me understand remote learning, and what it would be like for my students,” Alston said. “I would recommend the MSSST program to anyone I come in contact with who wants a master’s degree. The comradery I’ve had with this cohort, a network of teachers that have similar values and goals, has been huge.”

Whitney Beckstead, a fellow 2018-2020 MSSST cohort member, teaches chemistry and environmental science at American Fork High School. She got her bachelor’s degree in chemistry from the U and loved teaching, but wanted to go farther.

“The thing that’s been most impactful is learning about more science. The more I’ve learned, the more I’ve been able to make real-world connections to the subject I’m teaching,” she said, “Chemistry is everywhere, it’s part of life.”

Beckstead is doing research in Luisa Whittaker-Brook’s lab, which focuses on materials chemistry and nanotechnology. She’s analyzing a new material made up of both organic and inorganic components that conducts electricity, a property most organic materials are unable to do. She planned on conducting experiments herself, but now she’s analyzing data from past experiments.

“This summer working on the analysis, I would get stuck and have to ask for help, get feedback to make myself a better scientist,” Beckstead said, “I’m trying to teach my students that failure is OK, and failing quickly and learning from it is the most important part of science.”

MSSST alum shepherds Utah’s new science standards

Remote research corrects an idea many people learn in their K-12 education—that science is a list of linear steps called the ‘scientific method’ that must always be done in a lab. For Ricky Scott, K-12 Science Specialist for the Utah State Board of Education (USBE) and MSSST alum ’12, unlearning this idea was a revelation.

“After working in a genetics lab, I realized really quickly that when you give students a cookbook, step-by-step lab, you’re not doing authentic science. Scientists are generally not looking for the ‘right’ answer. They’re trying to better understand phenomena by asking, ‘What does this mean?’ or ‘How does this work?” Scott said.

In 2015, Scott Became joined the USBE to lead the transition towards new state science standards that encourage teachers to teach science by exploring questions to generate novel sense-making and authentic questioning. Scott is just one “MSSSTy” in science leadership in Utah—Salt Lake City School District, Granite School District and Alpine School Districts’ science specialists are all MSSST graduates.

“As we better understand how students learn science, we need to shift our methods. And science education research suggests that students need to be actively engaged in doing science,” Scott said. “My big desire to be a part of this transition for new state standards stems from my experience in MSSST. Engaging in research helped shift my classroom practice to a more authentic learning approach. This shift allowed me to observe the astounding effects that ‘doing science’ rather than simply ‘learning about science’ has on student learning.”