Do politicians act like humans? Many jokes suggest otherwise, but the question is real.

Groups of humans follow basic social rules: They build relationships, form alliances and exchange favors to help one another survive. In contrast, the stereotype of a politician is a person motivated by self-interest—the lust for power and re-election will supersede their human tendency towards collaboration. But legislators must cooperate to enact policy and survive in their political environment. So, do they operate under the same social rules as human societies across the globe?

Political scientists have recently utilized tools that anthropologists and sociologists have long used to study human behavior in groups. These “social network analyses” suggest that politicians pay great attention to their social environments. They tend to find friends with similar demographic and cultural traits (known as “homophily”) and build trust by taking turns helping each other (“reciprocity”). However, past studies have focused on competitive, high-stakes political institutions that receive national media attention…somewhere like the U.S. Congress.

For the first time, a University of Utah-led study assessed cooperation networks in the Utah State Legislature, an institution with a supermajority of legislators by both gender (male) and party affiliation (Republican). The authors asked a new question: Do Democrats and female legislators still choose to work with similar colleagues, even when Republicans and male legislators control the levers of power?

The study finds that despite the supermajorities, Utah legislators overwhelmingly initiate alliances with members from within their own political and gender groups. They also repay their social debts, reciprocating policy favors at high rates.

“There’s a whole swath of literature in biology and anthropology focused on the importance of building trust and relationships in constrained environments. And politically, the Utah State Legislature is one of the most constrained environments,” said lead author Connor Davis, a master’s student in anthropology at the U. “There are only 45 days in the session to determine a whole year’s worth of legislation. It’s chaotic. It’s a mess. But we still do it. So, how does that work?”

PHOTO CREDIT: Davis et. al. (2022). Human Nature

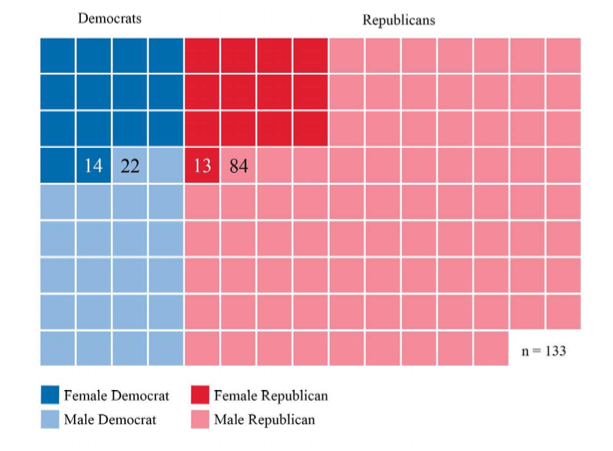

Utah State legislators organized by party and gender between 2005 and 2006. Each square represents one legislator. Values within squares denote total count of legislators with the same party and gender as the square color.

Download Full-Res ImageThe study was published on Feb. 17, 2022, in the journal Human Nature.

The Utah State Legislature has special rules for introducing legislation. Each bill can only have a single sponsor; legislators must enlist a colleague (a “floor sponsor”) from the other chamber to champion the bill in their respective chamber.

The researchers examined bill floor sponsorship in the Utah State Legislature from 2005-2008 and analyzed the characteristics that influenced who cooperated with whom. They looked at gender, seniority and party affiliation. They found that politicians were more likely to serve as a floor sponsor for a colleague of the same gender and political affiliation. Seniority in the legislature had no effect.

They also found lots of reciprocity—sponsors were likely to cooperate more in the future. Members of the same gender increased the likelihood that politicians would reciprocate. Surprisingly, party affiliation decreased the likelihood of reciprocation, suggesting that relationships built across the aisle were valued more and legislators kept a good standing with their colleague to collaborate into the future.

“In politics, you need to know how to play a game that has two sets of rules. There are explicit rules, as in the constitution, and the non-explicit rules, as in humans negotiating social relationships,” said senior author Shane Macfarlan, associate professor of anthropology at the U. “In Utah, you have to play both.”

Breaking the gridlock

The findings may be useful for understanding the rise of political polarization and gridlock in democracies internationally.

“There’s an idea that state legislatures such as Utah’s can at times be more bipartisan than Congress. Is that actually true?” asked Davis. “We can use these research tools to break down social networks at different levels of government and see how these personal relationships impact policy.”

The authors note that they looked at a single four-year time frame that was based on data availability of the Utah Legislature. They plan to pursue whether this is representative of other time frames. For example, do the findings hold during mid-terms versus presidential elections? Do extreme events such as economic downturns or natural disasters shift how politicians cooperate?

Additionally, the authors plan to analyze political cooperation across a diverse array of state legislatures that have different rules and demographics.

“We live in a politically divided time. At a national level, it’s deadlocked. But we have states running their legislatures using different kinds of systems and they produce different outcomes. Which ones produce the optimal outcomes, and which produce sub-optimal outcomes?” asked Macfarlan. “How do we want to construct state legislatures moving forward? It’s not going to be a silver bullet, but it’s some hard data that we can use.”

Daniel Redhead of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology was a co-author on the study.