Two professors in the U’s Department of Physics & Astronomy—Christoph Boehme, professor and chair of the department, and Ramón Barthelemy, assistant professor, have been elected fellows of the American Physical Society (APS). The APS Fellowship Program was created to recognize members who may have made advances in physics through original research and publication, or made significant innovative contributions in the application of physics to science and technology. They may also have made significant contributions to the teaching of physics or service and participation in the activities of the society.

Election to the APS is considered one of the most prestigious and exclusive honors for a physicist—the number of recommended nominees in each year may not exceed one-half percent of the current membership of the Society. APS is a nonprofit membership organization working to advance the knowledge of physics through its outstanding research journals, scientific meetings, and education, outreach, advocacy, and international activities. The APS represents more than 50,000 members, including physicists in academia, national laboratories, and industry in the United States and throughout the world.

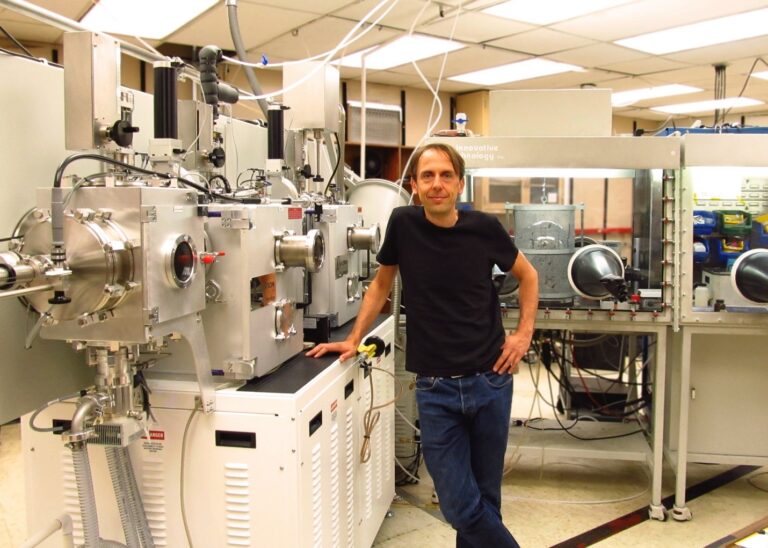

Christoph Boehme

Christoph Boehme, chair and professor, in his lab.

“I am profoundly honored by my selection as an APS Fellow. Receiving this recognition is an excellent opportunity to look back at my research career, starting with my first experiments as an undergraduate researcher more than 25 years ago. When I think about all the discoveries and inventions I have had the chance to contribute to, I realize that none of them would have happened without the collaboration, support, and collegiality of many others. These include my former research advisors, all the students and postdocs who have worked in my research labs, my colleagues at the U (both staff and faculty), and other institutions. I am very much indebted to all these wonderful people.”

Boehme was born and raised in Oppenau, a small town in southwest Germany, 20 miles east of the French city of Strasbourg. After obtaining an undergraduate degree in electrical engineering, and committing to 15 months of civil services caring for disabled people (chosen to avoid the military draft), he moved to Heidelberg, Germany in 1994 to study physics at Heidelberg University.

In 1997 Boehme won a German-American Fulbright Student Scholarship, which brought him to the United States for the first time, where he studied at North Carolina State University and met his spouse. In 2000 they moved to Berlin, Germany, where they lived for five years while he worked for the Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin, a national laboratory. He finished his dissertation work as a graduate student of the University of Marburg in 2002 and spent an additional three years working as a postdoctoral researcher.

Boehme moved to Utah in 2006 to join the Department of Physics & Astronomy as an assistant professor. He was promoted to associate professor and awarded tenure in 2010; three years later, he became a professor. During his tenure at the U, Boehme received recognition through a CAREER Award of the National Science Foundation in 2010, the Silver Medal for Physics and Materials Science from the International EPR Society in 2016, as well as the U’s Distinguished Scholarly and Creative Research Award in 2018 for his contributions and scientific breakthroughs in electron spin physics and for his leadership in the field of spintronics.

He was appointed chair of the department in July, 2020 after serving as interim chair. Previously, Boehme served as associate chair of the department from 2010-2015. His research is focused on the exploration of spin-dependent electronic processes in condensed matter. The goal of the Boehme Group is to develop sensitive coherent spin motion detection schemes for small spin ensembles that are needed for quantum computing and general materials research.

Ramón Barthelemy

PHOTO CREDIT: Matt Crawley/College of Science

Ramón Barthelemy, assistant professor.

Download Full-Res Image“When I started graduate school you couldn’t even ask the LGBT question in physics without ending your career,” said Barthelemy. “Although homophobia and transphobia are still rampant in physics, a few of us are lucky enough to ask the question and still continue in the field. It is amazing to get this recognition for my work considering the history of queer people in physics, from Alan Turing‘s death to the ending of Frank Kameny‘s astronomy career, and the inability of people like Sally Ride and Nikola Tesla to be public with all of their relationships. I am both humbled and full of gratitude to pursue funded work giving voice to queer people in physics and, importantly, changing policy.”

Barthelemy is an early-career physicist with a record of groundbreaking scholarship and advocacy that has advanced the field of physics education research as it pertains to gender issues and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT)+ physicists.

The field of physics struggles to support students and faculty from historically excluded groups. Barthelemy has long worked to make the field more inclusive—he has served on the American Association of Physics Teachers (AAPT) Committee on Women in Physics and on the Committee on Diversity—and was an early advocate for LGBT+ voices in the AAPT. He co-authored LGBT Climate in Physics: Building an Inclusive Community, an influential report for the American Physical Society, and the first edition of the LGBT+ Inclusivity in Physics and Astronomy Best Practices Guide, which offers actionable strategies for physicists to improve their departments and workplaces for LGBT+ colleagues and students. He also recently published the first peer reviewed quantitative study on LGBT+ physicists which received national attention.

In 2019, Barthelemy joined the U’s College of Science as its first tenure-track faculty member focusing on physics education research (PER), a field that studies how people learn physics and culture of the community. Since arriving, he has built a program that gives students rigorous training in physics concepts and in education research, qualities that prepare students for jobs in academia, education policy, or general science policy. He founded the Physics Education Research Group at the University of Utah (PERU), where he and a team of postdoctoral scholars and graduate and undergraduate students explore how graduate program policies impact students’ experiences; conduct long-term studies of the experience of women in physics and astronomy and of Students of Color in STEM programs; and seek to understand the professional network development and navigation of women and LGBT+ PhD physicists.

In discussing Barthelemy’s election as a fellow to the APS, two of his mentors, Geraldine L. Cochran and Tim Atherton, commented on his work: “Barthelemy has provided an excellent example for how research on the educational experiences of people from marginalized groups can center the voices of the research participants,” said Cochran, associate professor at Rutgers University. “Indeed, Dr. Barthelemy was among the first—if not the first—in physics education research to use Feminist Standpoint Theory in his research.”

“Fellowship is one of the highest honors that that American Physical Society can bestow and is normally reserved for scientists much further along in their careers,” said Atherton, associate professor of physics at Tufts University. “Ramón’s election is a signature of the incredible esteem in which his fellow physicists hold him and points to the significance of his work. This kind of work is necessary to transform the culture of physics to fully include LGBTQ+ people. As one of these people myself, and as someone who has not always been included by the academic community, I’m thrilled that Ramón has been given this incredible honor.”

Barthelemy earned his Bachelor of Science degree in astrophysics at Michigan State University and received his Master of Science and doctorate degrees in PER at Western Michigan University. “Originally, I went to graduate school for nuclear physics, but I discovered I was more interested in diversity, equity, and inclusion in physics and astronomy. Unfortunately, there were very few women, People of Color, LGBT or first-generation physicists in my program,” said Barthelemy, who looked outside of physics to understand why.

Other awards

In 2022, Earlier he received the 2022 WEPAN (Women in Engineering ProActive Network) Betty Vetter Research Award for notable achievement in research related to women in engineering.

In 2021, Barthelemy received the Doc Brown Futures Award, an honor that recognizes early career members who demonstrate excellence in their contributions to physics education and exhibit excellent leadership.

He received the 2020 Fulbright Finland award but wasn’t able to travel to Finland to give his lectures until 2022.

In 2020, he and his U colleagues Jordan Gerton and Pearl Sandick were awarded $200,000 from the National Science Foundation to complete a case study exploring the graduate program changes in the U’s Department of Physics & Astronomy. In the same year, Barthelemy received a $350,000 Building Capacity in Science Education Research award to continue his longitudinal study on women in physics and astronomy and created a new study on People of Color in U.S. graduate STEM programs. Later, he received a $120,000 supplement to continue the work.

He also co-received a $500,000 grant with external colleagues Dr. Charles Henderson and Dr. Adrienne Traxler to study the professional network development and career pathways of women and LGBT+ PhD physicists in academia, the government, and private sectors. Lastly, Barthelemy was selected to conduct a literature review on LGBT+ scientists as a virtual visiting scholar by the ARC Network, an organization dedicated to improving STEM equity in academia.

In 2014, Barthelemy completed a Fulbright Fellowship at the University of Jyväskylä, in Finland where he conducted research looking at student motivations to study physics in Finland. In 2015, he received a fellowship from the American Association for the Advancement of Science Policy in the United States Department of Education and worked on science education initiatives in the Obama administration. After acting as a consultant for university administrations and research offices, he began to miss doing his own research and was offered a job as an assistant professor at the U.