A poor diet and sedentary lifestyle drive up your chances of diabetes and heart disease—but it also makes it more likely that you’ll develop gastrointestinal cancers.

It seems obvious that unhealthy choices would contribute to an unhealthy gut, but scientists weren’t sure exactly why they increased GI cancer risk.

A team of researchers, led by the Department of Nutrition and Integrative Physiology’s Scott Summers, PhD, and Ying Li, PhD, have discovered that ceramides may serve as critical links between dietary macronutrients and cancer risk.

Ying Li, PhD and Scott Summers, PhD

Their article, “Ceramides increase fatty acid utilization in intestinal progenitors to enhance stemness and increase tumor risk,” has been published in Gastroenterology. Ceramides are a form of toxic fat with proven links to diabetes and heart disease. Summers and colleagues were surprised to discover that they can also change the gut in fundamental ways.

“The gut is amazing, it regenerates every four days and completely repopulates itself,” Summers says. “Dietary nutrients affect the process of gut regeneration. Saturated fat strongly affects intestinal stem cells, which produce gut cells. Too much saturated fat makes these cells divide too quickly, possibly causing polyps that can develop into cancer.”

Saturated fat can be converted to ceramides, and Summers’ team believes that blocking production of the toxic fat could ultimately prevent diabetes or heart disease. But they’ve now found that ceramides might serve as a key signal in the gut, causing cells to divide rapidly and create polyps, a precursor to GI cancers.

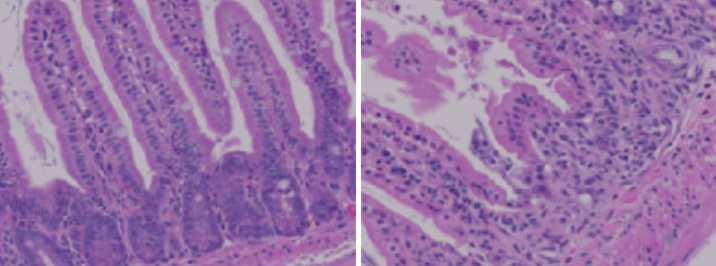

Ying Li originally worked with Summers as a postdoc at his lab in Singapore before moving with him to Salt Lake City. They lowered ceramides in various tissues of mouse models, but when they removed ceramides in the gut, the mouse models developed intestinal problems. Eliminating ceramides disintegrated the gut—a surprising result for the group.

A healthy mouse gut (L) and a mouse gut that is malformed (R) because it has insufficient ceramides.

Determining why that happened proved difficult. After lengthy experimentation, Summers was ready to move on, but Ying Li persisted.

“I got stuck in China due to some visa issues,” she said. “I was so stressed and couldn’t fall asleep at night, so I’d open my computer and look at the data and try to make sense of it.”

Finally, she wrote Summers a proposal. Saturated fat causes stem cells to proliferate, and Ying suggested this might be happening in the guts of the mouse models. In this case, removing the ceramides also removes a signal that tells stem cells to regenerate. So, instead of proliferating, they do the opposite. They disappear.

The unexpected result caused Ying to reason that blocking ceramides could become a powerful tool. “Now we want to see if we can modulate ceramides in stem cells to prevent cancer,” Ying said. “If that works, we hope to develop this into a new type of cancer therapy.”

Summers doesn’t consider himself to be a cancer researcher. But as he’s demonstrated with other diseases, ceramides change the way every cell type reacts to its nutritional environment. In this case, these toxic fats could be responsible for cancerous GI growth.

The investigation of ceramides as a potential cancer driver has earned Summers millions of dollars in grant money, seeding an enormous amount of activity in his lab. And it’s sparked collaboration across campus, specifically with Huntsman Cancer Institute.

Summers has teamed up with Mary Playdon, PhD, MPH, nutritional epidemiologist and cancer epidemiologist at Huntsman Cancer Institute and Neli Ulrich, PhD, MS, Chief Scientific Officer and Executive Director of the Comprehensive Cancer Center at Huntsman Cancer Institute, to block ceramides in mice and explore if they predict cancer in general.

His team has also worked with Bruce Edgar, PhD, stem cell biologist at Huntsman Cancer Institute, to research whether fruit flies have the same gut response. Ultimately, they were able to use their knowledge to prevent cancer in the flies—another small step toward solving a deadly problem.

“If ceramides really are the drivers of disease, we should be able to do something about it,” Summers said. “Drugs are being developed to slow ceramide production, but you can also envision dietary strategies that influence ceramide levels to slow cancer growth.”